Let’s talk about something seemingly unrelated to OCD: the Stockholm syndrome. Named after a situation in the early 1970s where people taken hostage at a bank started identifying with and defending their captors, the Stockholm syndrome is also known as capture-bonding. It is described in Wikipedia as “a form of traumatic bonding, which does not necessarily require a hostage scenario, but which describes ‘strong emotional ties that develop between two persons where one person intermittently harasses, beats, threatens, abuses, or intimidates the other.'”*

It’s hard to believe people could identify with someone who takes away all of their basic freedoms, but it unfortunately happens to 8% of victims, according to the FBI.

I think that the Stockholm syndrome is actually much more prevalent than that statistic would suggest. In fact, I would hazard a guess that it happens to almost everyone with OCD.

Sound crazy?

Let me explain.

A hostage and a voice

When I was developing the oral version of Is Fred in the Refrigerator?, I wanted to use a metaphor that adequately described how it feels to have OCD. Characters with OCD have had key roles in numerous TV shows and movies, but for me, those portrayals lacked the emotional depth needed to convey the utter hell that OCD creates in the mind and life of its sufferers.

It hit me as I was trying to go to sleep one night—a hostage crisis! That’s what it feels like to have OCD…like you are  being held at gunpoint 24/7. Thus was born the second story in the oral version of “Is Fred in the Refrigerator?”

being held at gunpoint 24/7. Thus was born the second story in the oral version of “Is Fred in the Refrigerator?”

I like metaphors, and another I created for “Fred” was WDNG, the radio station playing in my head and broadcasting “all danger, all the time…your home for the worst case scenario…all the bad things that can happen to you and the ones you love broadcast 24 hours a day, uninterrupted….for your listening hell.” In a recent Aha! Moment I talked more about WDNG and the demanding, deprecating voice that is OCD.

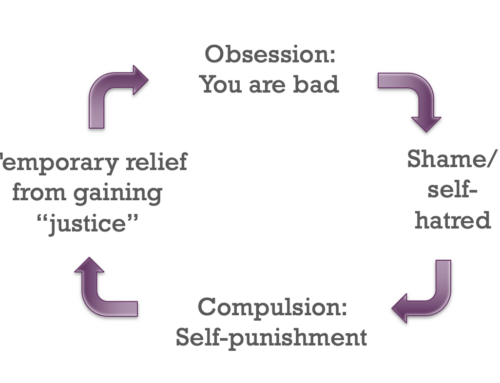

I know I’m not supposed to “mix metaphors,” but I can’t help it. If you put the hostage crisis and WDNG together, you get a really good idea of what having OCD is like: on one side of your head is the cold, hard barrel of weapon, which keeps you stuck doing your compulsions. On the other side is a vicious voice whispering not only obsessions in your ear, but also what a pathetic, shameful person you are for all the harm you are causing (if you have harm OCD) or how you must get whatever it is you’re doing, thinking, or feeling right (if you have just right OCD), or some lovely combination of the two.

I know I’m not supposed to “mix metaphors,” but I can’t help it. If you put the hostage crisis and WDNG together, you get a really good idea of what having OCD is like: on one side of your head is the cold, hard barrel of weapon, which keeps you stuck doing your compulsions. On the other side is a vicious voice whispering not only obsessions in your ear, but also what a pathetic, shameful person you are for all the harm you are causing (if you have harm OCD) or how you must get whatever it is you’re doing, thinking, or feeling right (if you have just right OCD), or some lovely combination of the two.

Sounds like fun, huh?

The OCD-induced Stockholm syndrome

Unfortunately, according to the International OCD Foundation, it takes on average14-17 years from the onset of symptoms for people to get the right treatment for OCD, either medication or a type of cognitive behavioral therapy called exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), or a combination of both. Which means that those of us with OCD live a long time (and I do mean a looooonnnnnnggggggg time) listening to that vicious voice and feeling like there’s a gun permanently pointed at our temples.

Let me remind you of a key phrase in Wikipedia’s definition of the Stockholm syndrome: “where one person intermittently harasses, beats, threatens, abuses, or intimidates the other.” To me, that sounds like a great description of what OCD does to the people who have it. Taking just a few choice examples:

“Can’t you be responsible and pick up that piece of trash? Someone could slip and fall on it, and it will be your fault! Won’t you feel awful if something happens that you could have prevented?!”

“Wash your hands again, you negligent oaf! You didn’t do it right the first [insert large number here] times, and you’re going to get sick and die if you don’t!”

“Did you just have a horrible image of a religious figure come up in your mind? What is wrong with you? Who thinks those things? Only people destined for hell, that’s who. I’d get on your knees and start praying for forgiveness if I were you!”

How would you feel after listening to that garbage all day long? Exhausted? Depressed? Beaten down? Like you just want it to stop? Yes, yes, yes, and YES.

So wouldn’t you think that once an OCD sufferer goes through ERP therapy and turns down the volume on OCD’s voice, that she would do anything she could to keep it quiet, so that she could be truly free?

You’d think so, but you’d be wrong. In so many cases, those of us with OCD develop the Stockholm syndrome: we take OCD’s vicious voice, and we make it our own.

The self-critical monster

I, unfortunately, have firsthand experience with having OCD-induced Stockholm syndrome. About three years into my recovery, I noticed that my inner dialogue about everyday stuff sounded an awful lot like the voice of OCD:

“You know that decision you made to buy your house all those years years ago? That was a terrible choice. You bought it at the peak of the bubble…don’t you know better? What were you thinking? I can’t believe how stupid you were.”

“Did you call your friend Jeannie back yet? You should have called her back right away. What kind of a friend are you? Not a very good one, that’s for sure.”

“Oh, great. You forgot to get milk at the grocery store again. Can’t you get it together? Come on, you’re an adult, for heaven’s sake, be more organized!”

Notice that the voice is not talking about anything that would be considered an OCD obsession. Nor is the voice really worrying about real-life situations, as someone with Generalized Anxiety Disorder might. Instead, it’s just telling me what an awful person I am. And what’s worse…it’s MY voice!

A demotivating motivational speaker

Because I lived with the voice of OCD sniping at me for decades, I unfortunately adopted its style as my own. My choice of how I treated myself was also reinforced by our pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps, push-yourself-really-hard-and-you’ll-make-it, always-find-a-way-to-improve American culture. I was used to OCD talking to me like that, and societal norms made me think that kind of inner voice would be motivating.

Dr. Kristin Neff’s book Self-Compassion: Stop Beating Yourself Up and Leave Insecurity Behind, debunks that  myth. In her chapter on motivation and personal growth, she says there’s a “widespread belief [that] we need to put a gun to someone’s head to make them do something unpalatable—especially when the someone is us.” Well, I can definitely relate to that!

myth. In her chapter on motivation and personal growth, she says there’s a “widespread belief [that] we need to put a gun to someone’s head to make them do something unpalatable—especially when the someone is us.” Well, I can definitely relate to that!

According to Dr. Neff, self-criticism does more harm than good for several reasons.

- It, like OCD, motivates through fear. But how well are we going to do when the anxiety resulting from that fear keeps us from performing at our best?

- Self-criticism undermines our belief in our abilities and causes us to lose faith in ourselves. Who wouldn’t start to lose confidence after being criticized over and over again?

- Finally, after years of blaming ourselves, we also might start to try to avoid the blame we’re inevitably going to dish out by self-sabotaging and procrastinating…that way we can blame outside forces instead of ourselves. “I was just so busy that I didn’t have time to prepare for the meeting…it’s my hectic schedule, and not me, that’s the problem.”

None of us, however, needs to live like this. As you might have guessed from Dr. Neff’s book title, another option exists: self-compassion.

Carrots, not sticks

On Dr. Neff’s website there’s a self-compassion assessment you can use to determine how self-compassionate you are. I took it earlier this year, and I scored a 1.81, which means I was low in self-compassion.

On Dr. Neff’s website there’s a self-compassion assessment you can use to determine how self-compassionate you are. I took it earlier this year, and I scored a 1.81, which means I was low in self-compassion.

By the way, as I was writing that previous sentence, I almost added “abysmal” before “1.81,” but caught myself before I used needless self-critical language. Instead, let me say that I scored about what I would expect for someone whose OCD has been hounding her for years. I’m going to give myself a break because I’ve been through hell with OCD, and of course someone who has been through what I have would score in that range!

That’s the point of self-compassion…to learn to be kind to yourself. I have been working on incorporating the three elements of self-compassion into the way I talk to myself:

- Mindfulness: I’m much more aware of when I hear that OCD-inspired vicious voice. “Wow, there I am talking like OCD again!”

- Common Humanity: I recognize that probably most people in my situation would think and feel similarly. “You know, I’m not alone here. I lot of my good friends have severe OCD, and any of them would feel exactly like I feel right now.”

- Self-kindness: I am giving myself a break much more often.

- “So I bought a house at the peak of the bubble….that’s OK. I made the best decision that I could at the time.”

- “I might not have called Jeannie back right away, but I called her the next day, and it’s not as if she had a stopwatch counting the minutes until I called her back!”

- “So I forgot the milk again….big deal! I’m busy, and it slipped my mind, and that is fine.”

Does this mean that I’m going soft on myself? That I’m just to let myself get away with anything? That I’ll lose any drive or ambition? No. This point is so important that I’m going to quote directly from Dr. Neff’s book:

We found that self-compassionate people were just as likely to have high standards for themselves as those who lacked self-compassion, but they were much less likely to be hard on themselves on the occasions when they didn’t meet those standards. We’ve also found that self-compassionate people are more oriented toward personal growth than those who continually criticize themselves. They’re more likely to formulate specific plans for reaching their goals, and for making their lives more balanced. Self-compassion in no way lowers where you set your sites in life. It does, however, soften how you react when you don’t do as well as you hoped, which actually helps you achieve your goals in the long run. (Neff, p. 168)

Recently I took the self-compassion assessment again, and I scored a 3.87, which means I am now high in self-compassion. What’s more important than my score, however, is how I feel: better. Which is only natural, considering that I am slowly but surely overcoming the OCD-induced Stockholm syndrome. Day-by-day, I am changing the way I talk to myself, dropping the harsh, critical tones and words favored by my OCD in exchange for self-compassion: mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness.

Recently I took the self-compassion assessment again, and I scored a 3.87, which means I am now high in self-compassion. What’s more important than my score, however, is how I feel: better. Which is only natural, considering that I am slowly but surely overcoming the OCD-induced Stockholm syndrome. Day-by-day, I am changing the way I talk to myself, dropping the harsh, critical tones and words favored by my OCD in exchange for self-compassion: mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness.

Not only do I feel better, but the more self-compassionate I am, the stronger my recovery from OCD will be. For me, thanks to ERP, the OCD hostage crisis has been over for almost ten years. The less I mimic the voice of my decades-long captor going forward, the more I can enjoy my well-earned freedom.

Update: since I published this blog in 2015, I’ve co-written a book about the use of self-compassion in the treatment of OCD with Jon Hershfield, MFT called Everyday Mindfulness for OCD: Tips, Tricks & Skills for Living Joyfully. I hope you’ll check it out!

Dutton and Painter as cited in Wikipedia, 1981.

[…] Source: https://www.shalanicely.com […]

[…] Be compassionate with yourself if you’re experiencing an increase in OCD symptoms. It’s not your fault! Do what you can to keep your compulsions in check without trying to be perfect. If you need support, schedule a booster session with your therapist or reach out to a support group like the IOCDF’s My OCD Community. […]

[…] to yourself! This is an incredibly challenging situation filled with myriad unknowns, and the more self-compassionate you are, the stronger you and your recovery will […]

[…] using the following tried and true recipe, of which I first learned in Dr. Kristin Neff’s book Self-Compassion, and that she learned from meditation teacher Shinzen […]

[…] Aha! Moments from Self-Compassion […]